Vincent B. Lortie

Data Scientist | Intact | Montreal, QC

Two years of learning Mandarin Chinese

This coming March will mark two years since I started learning Mandarin Chinese. Often, when this comes up in conversation, people ask me how I learn and practice. This post will tell you more.

How it started

For a long time when I was young I wanted to learn Chinese, but I never seriously considered the project because of the language’s reputation for being hard to learn. Around the beginning of 2022, the algorithm started feeding me videos about learning basic Mandarin Chinese, and this somehow generated enough interest and momentum for me to start practicing a little bit every day.

First month: Pinyin and pronunciation

Before I started learning Chinese, the aspect of the language I was most scared of was that Chinese is a tonal language. I was convinced that I would never be able to tell apart and properly pronounce the different tones.

I was also scared of failing, and I set the bar high: I didn’t want to be mediocre. If I were to learn Chinese, I wanted to speak it clearly, and I didn’t want to make mistakes.

Before I started learning any kind of vocabulary or grammar, I spent a month working exclusively on pronunciation.

Geeking out about sounds

The first thing I did was read up on Standard Chinese Phonology.

I looked at the list of consonants, then the list of vowels. For each sound, I would open the Wikipedia page (for ex. Voiceless bilabial plosive) and have a look at the Examples table. I would look for examples where the sound was used in either English or French, the two languages I speak, so that I could create a link between Chinese and sounds I could already pronounce. I would then learn to associate the Chinese pinyin (phonetic alphabet) with these sounds.

Speaking two languages made things a bit easier for me here: some Mandarin sounds exist in English, but not French, and vice versa. For example, the ü sound in Pinyin corresponds to the French u, but does not exist in English as far as I know.

Some sounds in Mandarin do not exist in either English or French (for ex. Voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate, the Mandarin j). These were a bit harder to learn: I had to figure out how to position my tongue and make the right sound. In the case of the Mandarin j, I put the tip of my tongue against the back of my bottom teeth and blew air through; similar to a “dj” sound in English, but with a different tongue position.

For those interested: I had the most trouble with the difference working on the difference between aspirated-unvoiced, unaspirated-unvoiced and unaspirated-voiced consonants. The different between p and b is not quite the same in English and Mandarin!

Then, for tones, I read about tone contours and learned to pronounce each for a simple syllable (e.g. ma):

- First tone is high and steady, as if singing a note

- Second tone is rising, as if surprised or asking a question

- Third tone is often described as falling-rising, but I’ve had more success seeing it as a low tone; you can even use vocal fry (think valley girl creaky voice)

- Fourth tone is descending

I also spent a bit of time learning about tone sandhi, which is how tones change when following each other. The most important to know is thatwhen you have two third tones in a row, the first one becomes a second tone. For more than two third tones in a row, it gets a bit more complicated.

By the end of this step, I understood how to read Pinyin and what sound each Pinyin syllable should make.

Practice practice practice

Once I understood how I was meant to pronounce each sound, I spent a full month practicing. The first week or two, I would use a Pinyin table like this one from yoyochinese.com to practice. I would go through each syllable, and each tone. I would play the sound recording and repeat out loud until I was confident I could reproduce the sound.

When I was confident in my ability to handle single syllables, I moved on to syllable pairs. Again, Yoyo Chinese had a great series of videos for this, starting with this video for pairs starting with the first tone. There are four such videos, each over 20 minutes long. The first few days, I would go through all four videos. I would listen to the pronunciation, then repeat. As it got easier, I started increasing the playback speed, up to 1.75x. Eventually, I started skipping parts of the video, doing only the first half of each tone pair.

This practice phase lasted about a month.

Getting pronunciation feedback

There’s only so much you can do on your own, and after all of this I was still worried I had it terribly wrong. My fear was that there was some key pronunciation point that I was missing because my ear was just not trained to pick up on the difference. I booked a few lessons with a local Chinese teacher, told her what I’d been doing, and asked to focus on pronunciation.

I half expected to have my world shattered and to have to start over. It turns out that what I’d been doing was not so bad. I received a bit of feedback, and more later from other people I spoke with. Overall, it seems like this approach had been enough to get me to a point where I could be understood, with a fairly standard pronunciation.

Vocabulary (HSK 2.0)

Ever since I started learning, the key to progress has been to practice a little bit everyday - 15 to 30 minutes - and the key to practicing everyday, for me, is twofold:

- Making my daily practice as mindless and effortless as possible, and

- Harnessing the motivating power of the “streak”

Making daily practice mindless and effortless

I used to swim 3 times a week at 7 in the morning. I think the reason this schedule worked so well for me was that I wouldn’t really wake up until my body hit the cold water of the pool. I would get up, but I wouldn’t be much more aware than a zombie until that moment. The key was that I wasn’t present enough mentally to think about what I was doing, and to ask myself if I really wanted to go swim that morning. When the alarm rang and woke me up, I would just automatically and mindlessly follow a series of motions that would ultimately lead me into the pool.

In a way, my approach to learning Chinese has been similar. The content of my daily practice is not something I can question: it’s predetermined, and I just have to do it.

I use Anki, a spaced repetition flashcard app. At their simplest, flashcards are cards with a question on one side and an answer on the other. You look at the question, you think hard about what the answer should be, and you turn the card over to see if you got it right. For example, the “question” could be a word in Chinese, and the “answer” could be its meaning in English. “Spaced repetition” is just the way Anki determines which flashcards you should review on a given day: its goal is to make you review a card just frequently enough to avoid forgetting, and no more.

This works for me because it takes any decision on my part out of the equation: Anki tells me what I need to review, and I review it: no more, no less. The only effort required is to open the app.

Learning materials

Those who use Anki know that I’ve left out an important part of the equation: where do the Anki cards come from?

Anki is just the software, the framework for learning. It’s not an app to learn Chinese. In fact, it can be used to learn many different things. Some med students use it for anatomy!

Based on what I’ve come across in the last two years, a lot of people seem to agree that the best way to use Anki when learning a language is to make flashcards out of situations you’ve encountered in your target language. For example, if you hear a sentence with a word you’ve never heard before, you can use that sentence as an example and make what’s called a “cloze deletion” card: a card where the question is a sentence with one word blanked out and the answer is the word that’s missing.

I don’t do this for one reason: it’s too much work if you want a steady stream of new cards. Basically, you would need to find regular opportunities to talk to people in your target language, or to read materials that you somewhat understand. You would then need to actively jot down sentences with bits that you hadn’t learned before, and create cards. This is almost as far from mindless and effortless as can be.

Instead, I use vocabulary lists. Sure, I learn a bunch of words I may not use for a long time, and without the context of a real situation I may not understand the words as well as I otherwise could’ve, but this method has one advantage: I can set Anki up to give me 5 new words everyday, and I won’t run out for years. I will learn new words continuously. If I don’t fully understand a word, it’s not the end of the world: when I first encounter it outside of my flashcards, I will at least be somewhat familiar, and this will allow me to better learn from the experience.

From March to December 2022, I used a deck of Anki cards I found online with the vocabulary from HSK 2.0, the second version of the HSK Chinese proficiency test. The deck can be found here, but you may need to make a few changes to its settings in order to display the questions and answers the way you like them. At first, I set it up to have two cards per word:

- Question: Pinyin + Example usage in pinyin; Answer: Definition + English translation of the example usage

- The above card, reversed

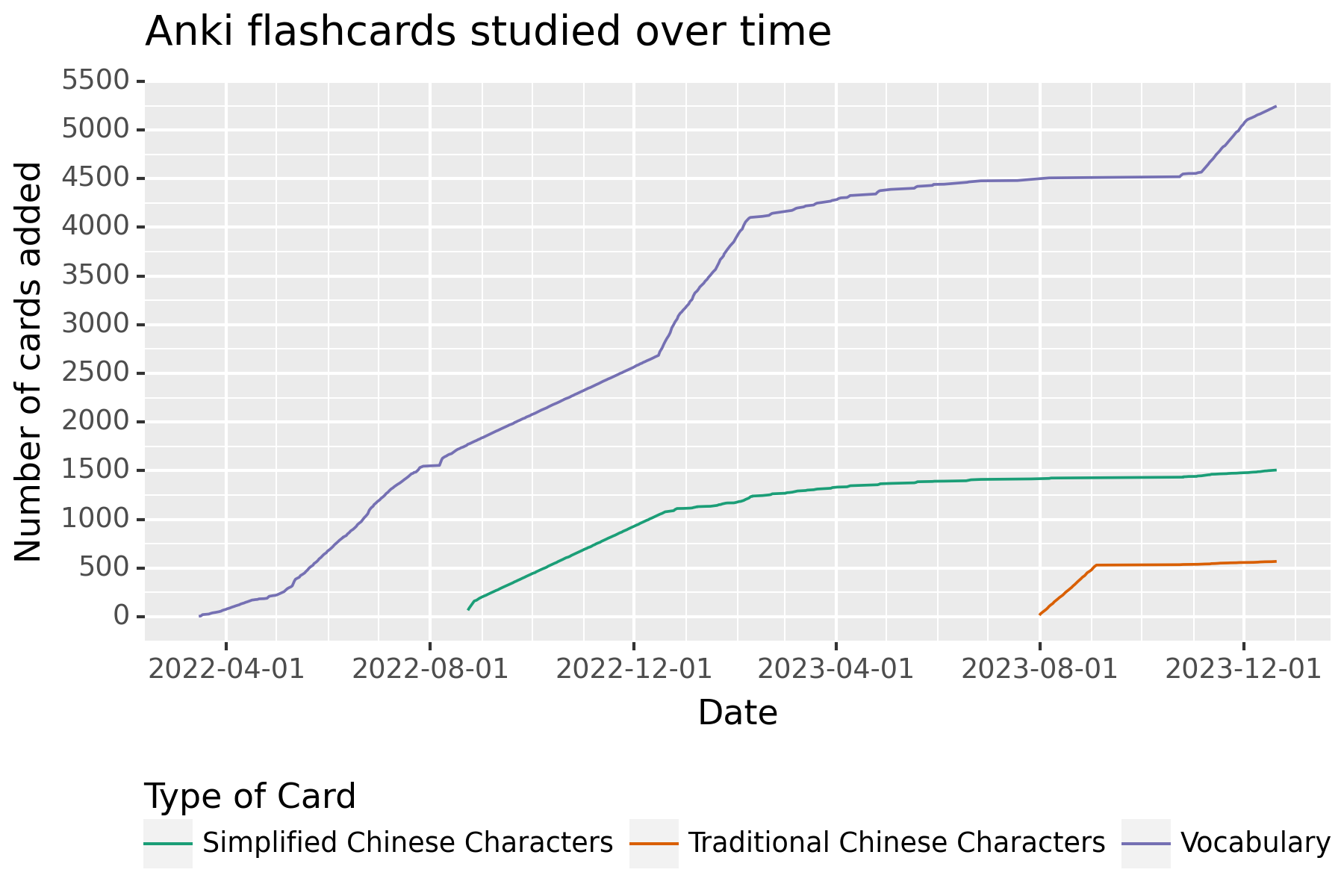

If I recall correctly, I set Anki up to show me 10 new cards per day. Since there were 2 cards per word, this corresponds to 5 words per day. The first 4 levels of HSK 2.0, in total, include about 1200 words. At the rate above, I had learned them all in 8 months. See the chart

The Anki streak

The first few weeks, I didn’t have much trouble keeping up with daily reviews for two reasons: I had the surge of energy that comes from starting a new project, and since I had only learned a few words there weren’t that many to review.

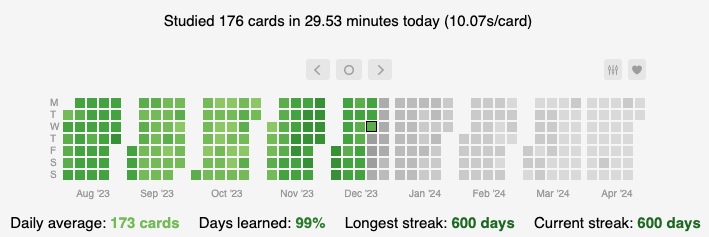

As time went on, three more reasons piled on: 1. I had started building the habit of doing these reviews everyday, so it came more and more naturally; 2. I could feel myself learning and understanding more and more; and 3. I had built up a significant Anki “streak”, the number of days without missing my daily review, that I did not want to break. 600 days later, the streak is still going:

Nearly two years later, this “project” of learning Chinese may not have the novelty that it had when I first started, and the feeling of learning more everyday has gotten weaker as each step of the learning journey takes progressively longer. I have been able to continue reviewing my scheduled cards everyday in part thanks to habit, but also because I know that I would never have progressed at this rate if it wasn’t for consistent daily practice.

Learning Chinese Characters

When I first started learning Chinese, I wasn’t too interested in learning to read Chinese characters; I mainly wanted to learn to speak the language. Reading sounded like a nice-to-have, and one that wasn’t worth the effort. I was also not sure whether or not I’d still be learning a few months down the line, so I figured I could always decide later to start learning to read.

A few months in, I had a discussion on a language exchange platform with a Chinese girl who lived in South Korea and had been learning Korean. She told me that she learned mainly through reading, and that she had made great progress in Korean by reading books. She strongly encouraged me to learn to read Chinese characters. I think the idea stayed in the back of my head, because around August 2022 I started learning to read.

I chose to learn simplified rather than traditional characters mostly because there are more Mandarin speakers who use simplified.

First attempt: Flashcards

At first, I figured I would do the same I had done for vocabulary: reviewing Anki flashcards on the computer screen. I would look at a Character and try to remember what it was, then check my answer against the back of the card. I wrote a python script that connected to the AnkiConnect API, a plugin which allows interacting with Anki using the programming language of your choice. This script went through the list of cards I had already learned and extracted all the Chinese characters I had failed to learn, then created a card for each of these characters. My cards for Chinese characters are a bit different: on the front, there’s the character, a word in which it is used, and a sentence that uses this word, all in Chinese characters. On the back, the Pinyin, along with English translations. Later, I added an animated SVG that showed the stroke order of the character on the front of the card.

It took only a few days to realize this wasn’t going to work. When reviewing vocabulary, I usually remembered most of the words I had learned the day before. Chinese characters, however, just wouldn’t stick: I had trouble remembering any of them. Because of how often I would forget the characters, my Anki reviews were piling up.

In addition to this, I gave myself a goal to learn all the Chinese characters that made up my vocabulary by the end of the year, less than 5 months later, while I simultaneously kept expanding said vocabulary. If I wanted to reach that goal, I would have to either study for multiple hours every day, or find another way.

Second attempt: Flashcards + Handwriting

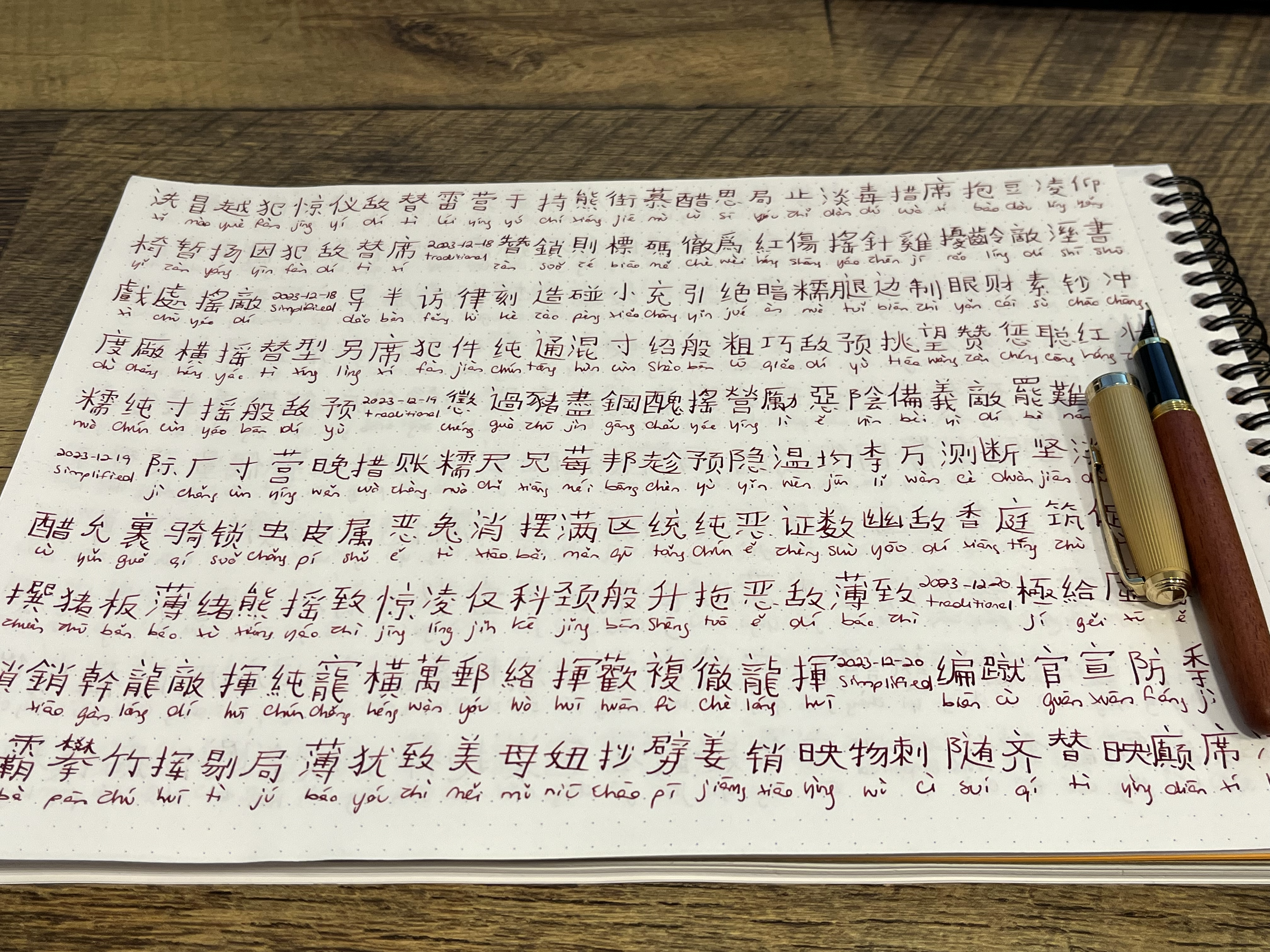

The solution came in the form of handwriting: for each character flashcard I would review during my daily practice, I would handwrite the character as part of a word. For example, the characters 喜 and 欢 together form the word 喜欢 (to like): whenever the flashcard for either word would come up, I would handwrite the whole word 喜欢. It’s only months later, after learning hundreds of characters, that I stopped writing these full multi-character words, and started writing only the character that appeared on the card.

My practice notebooks ended up looking something like this:

Not long after I started, I started using up all of the ink in my ballpoint pens, so I ordered a $10 refillable fountain pen, pictured above, and a bottle of ink.

Picking up traditional characters

Nearly a year after I started learning simplified characters, I started planning a trip to Hong Kong and Taiwan. I knew speaking Mandarin wouldn’t be of much use in Hong Kong, where Cantonese is the main language and where most speak English. However, I thought I may be a bit less disoriented in both Hong Kong and Taiwan if I learned traditional characters.

At this point, I had learned a bit over 1500 simplified characters. Of these 1500, a bit less than 1000 were the same in simplified and traditional, leaving me with 500+ new traditional characters to learn. With only a bit more than a month to spare before the trip, I created an Anki deck out of these 500+ characters, and set out to learn around 20 characters per day. I don’t quite remember the exact rate, but it was just enough to catch up to my simplified level before the trip.

Traditional characters turned out to be much easier to learn given that I had already learned the simplified equivalents. Many of the changes between traditional and simplified characters are systematic. For example, the component on the left of 説, which becomes 说 when simplified. Once I had picked up on a few of these patterns, the meaning of some traditional characters became obvious. If it wasn’t for these systematic changes, it would have been much more difficult to learn so many characters in such a short time.

Readers with a keen eye and those who can read Chinese will have noticed that the picture of the notebook above has both traditional and simplified characters, in separate sections. I still practice both separately to this day, learning simplified first, then learning only the traditional characters that are different from their simplified equivalent.

Zoom lessons

TODO

Switch to HSK 3.0

The end of the year 2022 was a turning point in my journey: around the same time, I finished learning the vocabulary for level 4 of HSK 2.0 and I caught up my knowledge of characters to my vocabulary. On top of that, the vocabulary list for HSK 3.0, the new version of the HSK language proficiency test which had been in development when I started learning, had recently been released.

I took some time to compare the new HSK to the old I had been using and noticed a key difference between the new HSK 3.0 and the old HSK 2.0 I had been using: the approach to vocabulary and characters. For the same number of characters learned, HSK 3.0 teaches a lot more words. Let me explain: Chinese characters can combine in many different ways to form words. A word is most often 1 to 3 characters long. A character can have more than one meaning, and the different meanings typically come out when that character is combined with other characters to form different words. When I started looking at the HSK 3.0 vocabulary list, I noticed something: there were many words I had never learned, but that were nonetheless made up entirely of characters I knew. Compared with HSK 2.0, HSK 3.0 offered many more examples of how to combine together the characters it teaches.

This is obvious when you look at the number of words and characters learned at a given level in both versions of HSK. By level 5 of HSK 2.0, a learner would know 1685 characters and 2500 words. By level 6 of HSK 3.0, a learner would know a few more characters, 1800 in total, but more than double the number of words, 5456 in total.

HSK 3.0 was also much more recent and, therefore, modern. I was surprised to see words like 传真 (a fax) taught in beginner HSK 2.0 levels.

At this point, the only reason I had to stick with HSK 2.0 was that I had a ready-made Anki deck. I stumbled upon krmanik/HSK-3.0-words-list, which provides the HSK 3.0 word list in TSV format along with definitions from Wiktionary and CC-CEDICT. From there, it was easy to create flashcards. I spent a bit of time going through the spreadsheet and selecting an interesting usage example from the dictionary definition of each word, then wrote a Python script that parsed the spreadsheet and created Anki cards from its contents, along with cards for the characters I would have to learn.

Over the course of a bit more than a month, I learned nearly 600 words from this list. I could afford to learn nearly 20 words everyday because most of these words were just new permutations of characters I already new.

HSK pause and new sources of vocabulary

In February 2023, I put the HSK vocabulary lists on hold. The main reason was that I wasn’t satisfied with the usage examples I could find within vocabulary definitions, and as a result found the quality of my new HSK 3.0 Anki cards lacking.

I also had more work on my plate preparing and reviewing for my Zoom lessons, during which I would discover many new words. This became my main source of vocabulary: I would take a word I learned either during class or while reading an article for class, and create a cloze deletion flashcard from it, using the context in which I learned the word for the cloze.

Enter GPT

Sometimes, the context in which I learned a new word wasn’t exactly suited to writing a cloze deletion flashcard, and I couldn’t think of a good sentence to write on the flashcard. Around this time, ChatGPT was launched, and it quickly became clear how much potential it had to change language learning.

I wrote a small Python script to which I could feed a list of words. The script would then, for each word in the list, call the GPT (3.5 at the time) API in order to generate examples of how to use the word.

Here’s the prompt I used at the time:

prompt = \

f"""Give me {n_examples:d} examples of sentences that use the expression "{expression}" in Mandarin and illustrate its meaning.

Format your answer as a JSON array where each example is an object containing

a field called "simplified": the example in Chinese simplified characters

a field called "pinyin": the same sentence in pinyin",

and a field called "english": the sentence's English translation.

"""I would then go through the output of the script and select the best example out of all 3 for each word, and create an cloze deletion card from it.

HSK, GPT, DALL-E, and a homemade Anki card builder

This takes us to the latest changes I’ve made to my learning process. Recently, I decided I needed more systematic progress, and I returned to the HSK 3.0 vocabulary list. I wanted to change it up a bit from the way I used to do things when I last studied HSK 3.0: I wanted more effective flashcards.

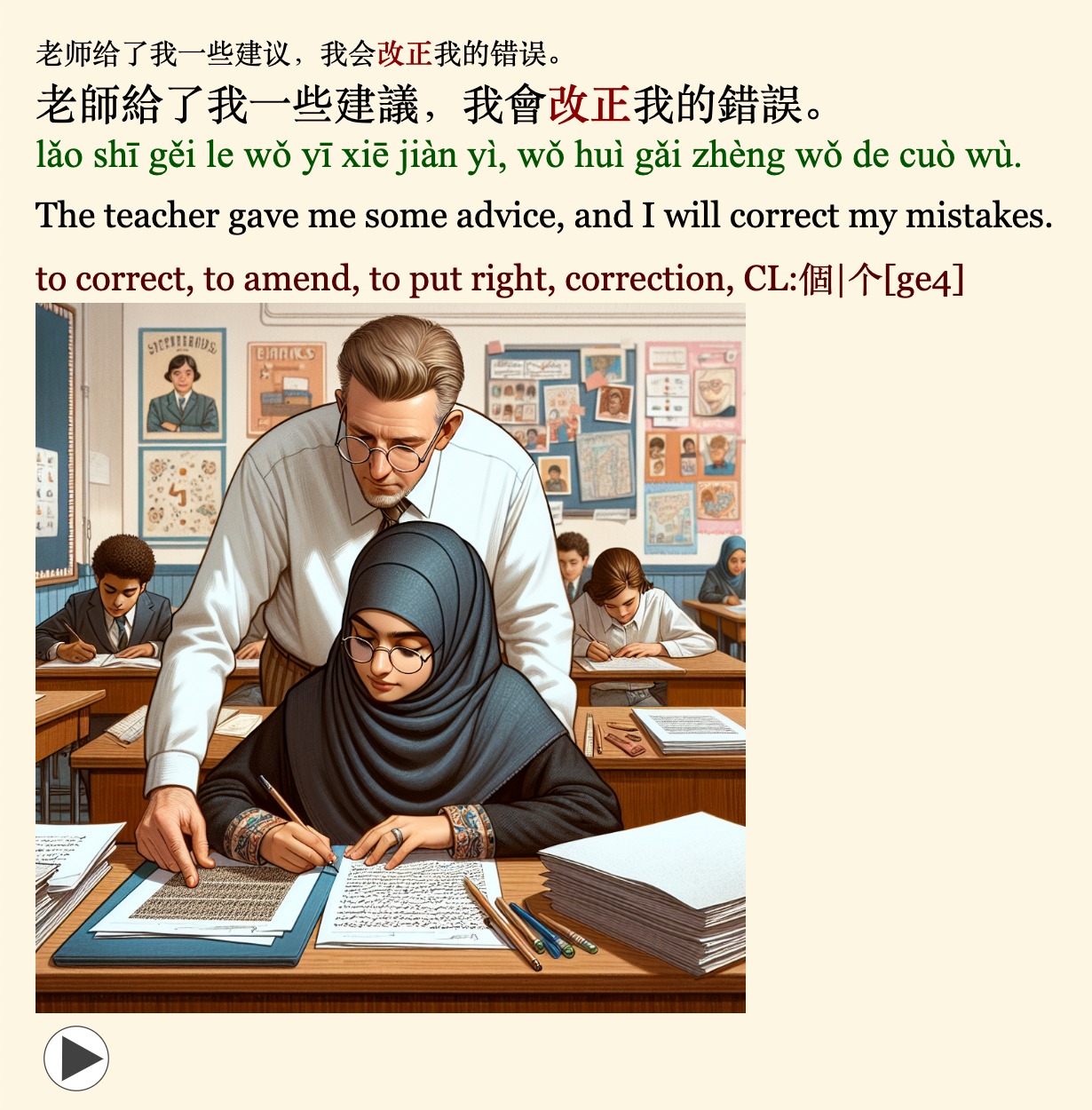

I developed a small app that I run on my laptop and that helps me build Anki cards for HSK 3.0 vocabulary.

When I open the app, I see on the left a list of all HSK words for which I haven’t yet built a card, ordered by level. This allows me to select the next word on the list and use it to create a new card.

When I select a word, the app asks GPT 3.5 to generate 3 examples of how to use this word. The GPT prompt is similar to what I show above, but I have since changed it to use traditional characters, and my flashcards ultimately have both sets of characters. If none of the 3 examples satisfy me, I can generate more until I find an example that I like. I can then edit the examples by hand or use them as-is.

Then, the tool lets me call DALL-E, another OpenAI model, to generate an image. Here, I write the prompt by hand to get an image that represents the example sentence well. The image is automatically attached to my flashcard.

The result is, for each HSK word, one or more new flashcards:

- A cloze deletion card where I see the example sentence with the word missing and I have to remember the right word to use

- A card for every new simplified character that appears in the word

- A card for every new traditional character that appears in the word, if different from the simplified character

In addition, the flashcards include DALL-E images (when relevant) and an audio rendering of the sentence Google’s Wavenet voice synthesis models.

Progress to date

The graph below shows how many cards I have learned through time in my Anki decks for vocabulary, simplified characters, and traditional characters. For character decks, the number of cards matches to a number of characters. For vocabulary, it’s not quite that simple. At first, each word had two cards. Eventually, I started adding more and more cloze deletion cards, with a single card per word or expression.

Next steps

As of writing, I have started studying level 4 of HSK 3.0. The sudden increase at the end of the graph above reflects what I have learned so far.

I have set myself a goal for 2024: Maintain my current rate of 8 new words per day, and learn all the vocabulary of the next 3 HSK levels (4-6) before the end of the year. By my estimates, I should:

- Finish HSK 4 by end of February

- Finish HSK 5 by end of June

- Finish HSK 6 by end of October